Pete Barr & Eli Heath

Product designers, Founders of Enayball

Pete and Eli met at the University of Brighton where they were studying product design. As part of a volunteering project for the charity Remap, they created a device to enable a wheelchair user with Multiple Sclerosis to produce art.

The experience opened their eyes to the need for accessible, beautifully designed devices to support people with disabilities and Enayball (pronounced enable) was born.

“I think all good design solutions come from a real world problem and Enayball certainly did.” says Eli Heath, co-creator of the electronic device that makes producing art accessible to all.

Enayball began life when Eli and his co-founder Pete Barr were studying product design at the University of Brighton. The pair volunteered with Remap, a charity dedicated to designing and creating custom-made equipment to help disabled people lead more independent lives.

The duo were asked to create a device for Barry, who was paralysed from the neck down by late onset multiple sclerosis. He wanted something that would allow him to be creative and make art.

Their first version was “essentially a big ballpoint pen on a stick,” laughs Pete. “The ballpoint pen – because it was oversized – was made from a roll-on deodorant ball. It worked really well, but because the ink was mixed with the deodorant it never dried…and smelled really weird.”

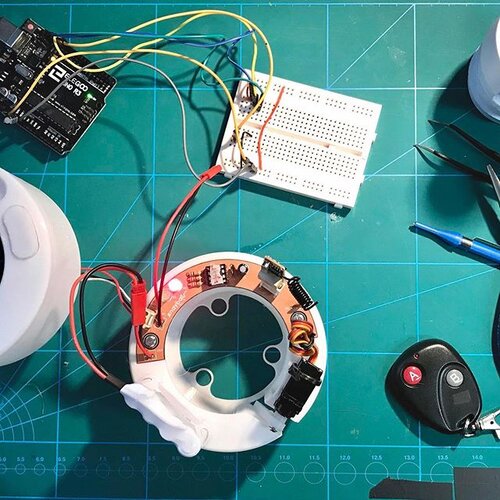

Enayball has come a long way since that early prototype. Now, the sleek white and yellow device can be attached to a wheelchair via an articulated arm. This enables people to create large scale art pieces on the floor. There’s also a hand-held tabletop version too.

Thanks to its electronic stabilisation, it glides effortlessly across paper or canvas and can hold everything from a biro or paintbrush to a chunky piece of chalk and can be controlled in different ways to suit a range of abilities.

“Something that has been a real goal from the beginning for both of us was to challenge design stereotypes of disability products,” says Eli. “You see a lot of disability aids that have a boring, utilitarian design. We want Enayball to be hyper functional, but also a product you’d be excited to receive for your birthday.”

Pete agrees: “I’m really interested in the world of socially-led design, creating things that actually help people rather than just producing products that can be sold and Enayball is a really great way of being part of that world. For me, the most important thing about this project is sticking to the vision behind it: to make art accessible to everyone.”

The pair work through an iterative process, with rounds of research, testing and refining of prototypes to fine-tune the design. “People think of product designers as mad inventors sitting by themselves in a room and coming up with new light bulbs or whatever,” says Pete. “That’s the stereotype. But it really isn’t like that.”

Instead it’s a collaborative effort that places people – particularly potential users – at the heart of the design process. It can often be an illuminating if occasionally frustrating experience: “When someone holds it in a way that you haven’t been holding it, that offers a true insight.” says Pete.

The feedback from users has been hugely positive – not just in being able to make art, but in offering them an opportunity to regain some agency in their lives. “It started as a very personal one-off design solution for Barry,” says Eli. “We’d never designed anything with so much social benefit before and watching him use it was just electric. The significance to him, and to us, was massive.”

“We want the act of art creation that comes from Enayball to re-frame ‘disabled artists’ as simply ‘artists’. We want it to start a conversation around disability and accessibility,” says Eli. “So a huge part of this is smashing stereotypes.”

Click here for more scientists who are Smashing Stereotypes.